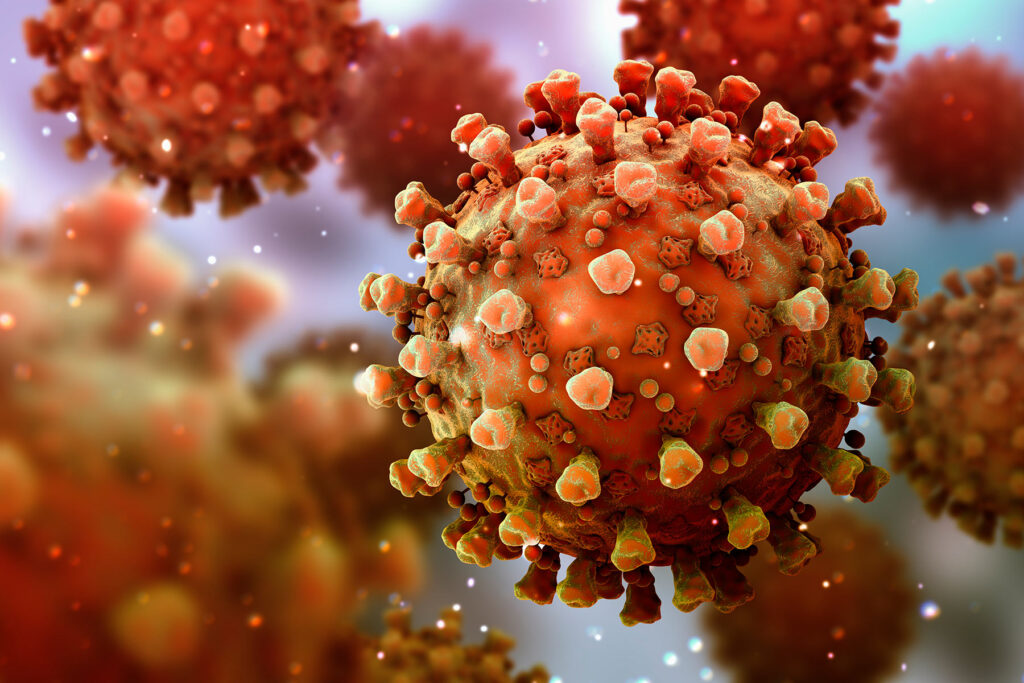

New Mutation Sped Up Spread of Coronavirus

Nov. 13, 2020 — The virus that causes COVID-19 is not the same strain as what first emerged from China. A new study shows it has changed slightly in a way that makes it more contagious to humans.

Compared to the original strain, people infected with the new strain — called 614G — have higher viral loads in their nose and throat, though they don’t seem to get any sicker. But they are much more contagious to others.

“That kind of makes sense,” says Ralph Baric, PhD, a professor of epidemiology, microbiology, and immunology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The new strain has a change to its spike proteins — the regions of its outer shell that dock on our cells and infect them. The change makes it a much more efficient predator. It passes quickly from cell to cell in our bodies, copying itself at a furious pace.

Baric’s experiments help to explain why the 614G strain, which first emerged in Europe in February, has quickly dominated worldwide spread.

He says the virus likely jumped out of bats and discovered a brand new population of human hosts, with more than 7 billion of us on the planet to infect. None of us has any immune defenses against it, so we are prime targets. Viruses with genetic advantages that help them copy themselves faster and jump more quickly between hosts are the versions that survive and will get passed on.

“So it can jump from person to person to person to person, that’s going to be the most competitive virus in terms of the virus maintaining itself,” says Baric, who is one of the world’s foremost experts on coronaviruses. His new study is published in the journal Science.

The new study backs up earlier research by a team of scientists led by Bette Korber, PhD, at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. The team first noticed the rapid spread of the new strain and questioned whether the virus wasn’t evolving to become more easily passed between people.

In new experiments, animals infected with the new 614G strain passed it much more quickly to healthy animals than those infected with the original strain.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin in Madison infected 16 hamsters with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Eight hamsters were infected with the new 614G strain. Eight others were infected with the original strain that was first identified in China. Each infected hamster was paired with a healthy hamster that was separated by a partition in a cage, so that the animals couldn’t touch but did breathe the same air. By the second day of the experiment, five of the eight healthy hamsters sharing air with animals infected with the 614G strain had fallen ill and were shedding the virus themselves, but none of the healthy hamsters paired with those infected with the original strain had gotten sick. The original strain did eventually sicken the healthy animals, but it took 2 more days for that to happen, proving that the changes helped to speed the spread of the virus

Baric and his team also wondered if the changes to the structure of the virus would affect how future therapies — including a vaccine — might work against it, since all the treatments now in development have been designed to counter the original strain that emerged from China.

They tested antibodies extracted from the blood of people who had survived COVID-19 infections on both the new and old strains, and they found no significant differences in how well those antibodies worked to neutralize the virus.

That’s good news, because it means people who recover from an infection with the original strain might still have some protection against the new strain.

In the U.S., the original strain was imported from China and began circulating on the West Coast, while the new strain was imported from Europeans who were mainly traveling to New York and the rest of the East Coast.

Baric and his team also tested the antibodies that are being developed as treatments to give people passive immunity against the virus. Those seemed to work well, too.

“The vaccines, which are all based on the original Chinese strain, make a good immune response that protects against this strain, so that’s good news,” he says.

While current treatments and prevention efforts don’t seem to be affected much by this change to the virus, the mutation does raise questions about how fast new strains are emerging and whether or not one of those might cause a problem in the future, Baric says.

Coronaviruses, as a group, are extremely stable. They have a special molecule — rightly dubbed a proofreader — that makes sure the virus gets copied correctly.

Because of this proofreader, the speed of the emergence of these new strains of the new coronavirus has been somewhat surprising to scientists who study them.

One development that Baric and other scientists are closely watching is the emergence of new strains found on mink farms in Denmark and the Netherlands that have been shown to infect humans.

There’s work being done to confirm that at least one of those strains — the so-called cluster 5 virus — may have evolved enough changes to its spike proteins that help it escape the vaccine.

Baric says the research needs to be verified, but early work suggests that the virus appears to have changed to help it infect minks more efficiently, while also keeping its ability to infect humans.

When a virus evolves in a way that allows it to circulate in an animal species, “it becomes more difficult to eradicate that virus,” he says.

Baric says if the virus continues to be passed in minks, if we vaccinated everyone in Denmark, but left the minks, the virus would hang out until there were enough new, susceptible hosts — typically young children — and then jump back into humans.

For that reason, he says mink farms may need to take further steps, like vaccinating their animals, or, in the worst case, killing their minks, to control the spread.

WebMD Health News

Sources

Ralph Baric, PhD, William R. Kenan Jr. distinguished professor, Department of Epidemiology, and professor, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Science: “SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant exhibits efficient replication ex vivo and transmission in vivo.”

Cell: “Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID19 Virus.”

© 2020 WebMD, LLC. All rights reserved.

Source link